Background: The ‘civics’ part aka the “two party” system:

Dominance in the House of Representatives:

The House of Representatives (aka ‘the Reps.’ which is the ‘lower’ house of the Australian Parliament) presently has 151 members – 76 members required for a majority. Electorates have a small population typically around 100K voters (currently, the smallest, Lingiari, has just 65K electors and the largest, Canberra, has about 144K

Australia’s electoral system uses preferential voting (aka ‘alternative voting’) for elections to both houses of parliament. In the Reps, this system has tended to entrench power in the hands of one of the two dominant parties, the Australian Labor Party (the ALP) & the Liberal/National Parties (a.k.a. ‘Coalition’) as the small population of any electorate has a tendency to dilute a minority party’s voters, ‘cracking’ them amongst seats in such a way that they are seldom likely to win the most votes in any given seat.

Thus either the ALP or the Coalition tend to receive a majority of votes in each seat in the House or Representatives and it is exceedingly rare for the governing party to not hold a majority, occurring only twice since 1943 (the 2010 Gillard & 2018 Morrison governments). Minor party candidates are rarely elected to the House of Representatives – by my count, only 20 minor party or independent candidates have been victorious in seats since 1946.

Irrelevance of the Senate (for the purposes of originating climate change action):

The Upper house (the 76 member Senate) also uses preferential voting but more accurately reflects voters intent (splitting voters into a small number of states rather than 151 districts, a normal election sees votes elect the six candidates with the highest vote share in each state).

However, the senate tends to act as a ‘house of review’ and seldom originates legislation, because:

“…Bills which authorise the spending of money (appropriation bills) and bills imposing taxation cannot originate in the Senate. The Senate may not amend bills imposing taxation and some kinds of appropriation bill, or amend any bill so as to increase any ‘proposed charge or burden on the people’ but it can ask the House to make amendments to these bills…”

Source: APH info sheet 7 – Making Laws

As most effective climate action requires either spending money or imposing a price signal/tax on carbon pollution, the senate is of secondary consideration (although the senate notoriously blocked action on climate change on at least one occasion).

Also, while it is technically possible for Reps legislation to come from a private members bill (bills from backbenchers, minority parties or the opposition) this has rarely happened in practice:

“…Since Federation 30 non-government bills have passed into law—23 introduced by private Members or private Senators and 7 by the Speaker or President of the Senate…”

Source: APH Infosheet 6 – Opportunities for private Members

Only two Private Members bills were adopted in the recent 45th parliament, the first being a bill on Marriage equality by Senator Warren Entsch (a government back-bencher), and the second, the controversial ‘medevac’ bill, passed by parliament in February 2018 against the wishes of the Morrison minority government, the first such loss to a government in the house of representatives since 1929

The usual fate of private members bills is to lapse (dying in committee or having debate deferred) or to be withdrawn. So we can probably discount the possibility of action arising from a private members bill.

And so…

Legislation tends to originate in the Reps, from either one of the dominant parties (ALP or Coalition) whose majority allows them control of the agenda, passing their own bills and closing debate on other bills.

So what influences the dominant parties, and what might be dissuading them from acting more on climate change?

Influences on dominant parties:

Interest groups influencing our two dominant parties can be broken down into:

- electorates voters,

- external lobbyists.

- political parties & ideology

Interest Group1: the voters! (jobs & $ for services):

Revenue – royalties and corporate taxes:

Mining is a major contributor to Federal and State coffers. For example, royalties of over $5 billion for QLD and $1.8 Billion for NSW in 2018 – similar revenue to that attributeable to taxes on the gaming industry.

Federal corporate tax payable for all mining companies with an income over 100M, based on Tax transparency: reporting, seems to be approximately $4 billion in the 2017-2018 financial year. Forgoing all of this revenue would require governments to borrow, implement unpopular service-cuts or new taxes…

While a disincentive, this would not be an insoluble problem (after all, the Carbon tax collected $15.4 billion in revenue in it’s few years in operation) and it seems unlikely to be driving force behind inaction.

Export Income:

Coal is on track to be Australia’s most valuable export in 2018/19, potentially reaching $67 billion, equivalent to 3.5% of nominal GDP.

However, it’s debatable how much benefit Australia is reaping from this trade – our overwhelmingly multinational coal mining companies seem adept at tax minimisation (e.g: Glencore & again Glencore) and while some revenue undoubtably flows into Australians hands via dividends, capital gains in super funds etc, but it’s difficult to determine how much of the earning stay in Australia. For example, some reports suggest that 79% of all Hunter Valley coal mines in 2014 were entirely foreign owned with only two majority Australian owned and only six with any substantial Australian ownership.

Also, it has been argued that huge mining exports may be undermining the rest of the economy (the so-called ‘resource curse’) by keeping the Australian dollar artificially high – here’s the Reserve Bank on the mining boom:

“…It has also led to large changes in relative prices, most noticeably an appreciation of the exchange rate. The combination of changes in income, production and relative prices has meant large changes in the composition of economic activity. While mining, construction and importing industries have boomed, agriculture, manufacturing and other trade-exposed services have declined relative to their expected paths in the absence of the boom…”

Discussion Paper – The Effect of the Mining Boom on the Australian Economy

Employment:

Conservative politicians often stress that coal mining is is a major employer, directly providing 54,000 jobs – the ABS estimates the number as more like 38,100 jobs. To put this in perspective, a single company in banking, Westpac, employs more people in Australia than coal mining.

However, while coal mining is a small employer nationally, it is a significant employer locally concentrated in and around the handful of seats where it operates, directly supporting sizeable portions of the electorate with well-paying jobs and indirectly stimulating employment via economic activity and local-buying programs. By contrast, jobs in renewables (reaching 17,740 in 2017/2018) are likely to be widely dispersed amongst electorates due to the the dominance of rooftop solar in renewable employment.

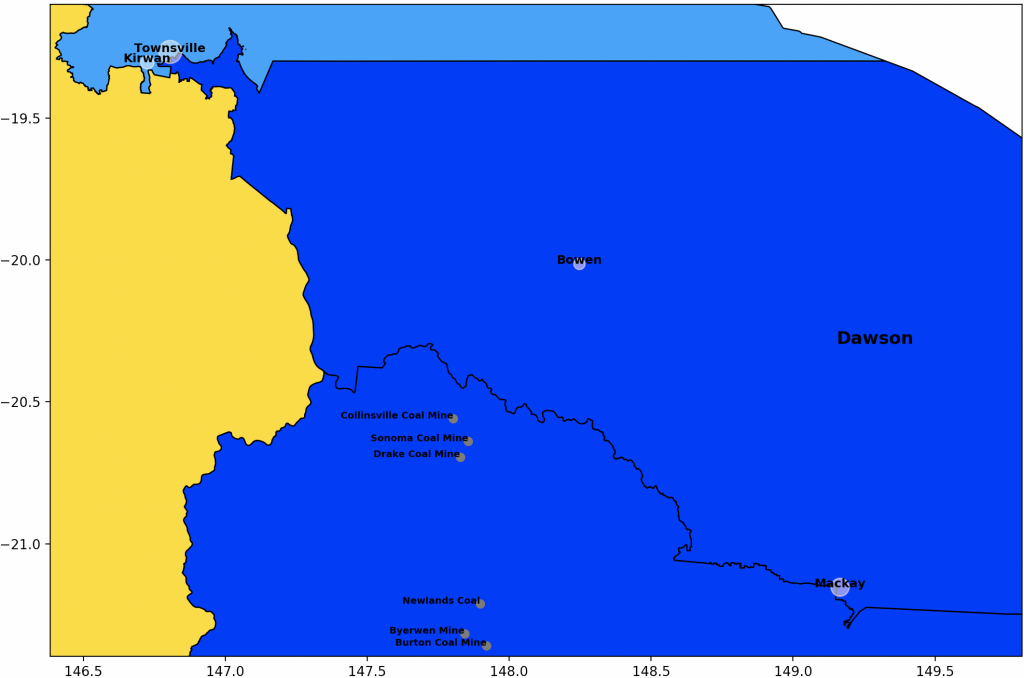

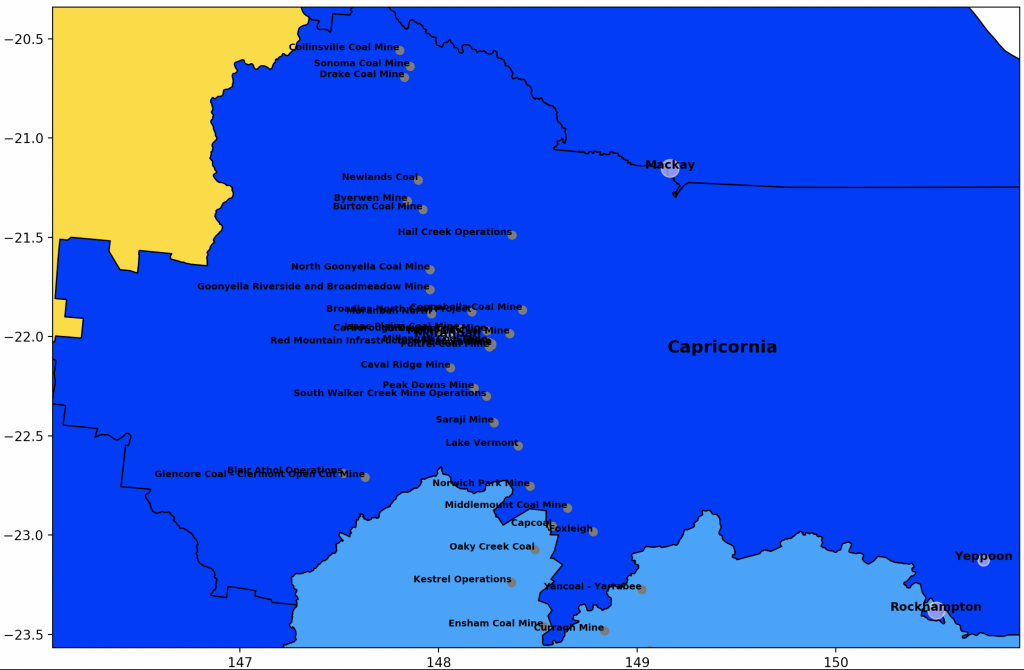

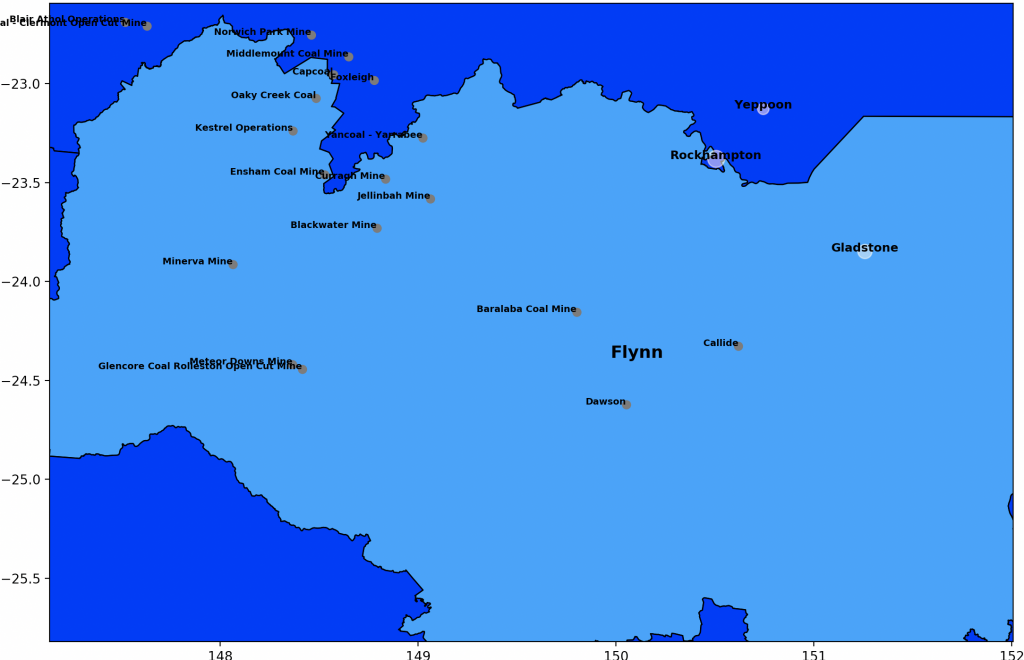

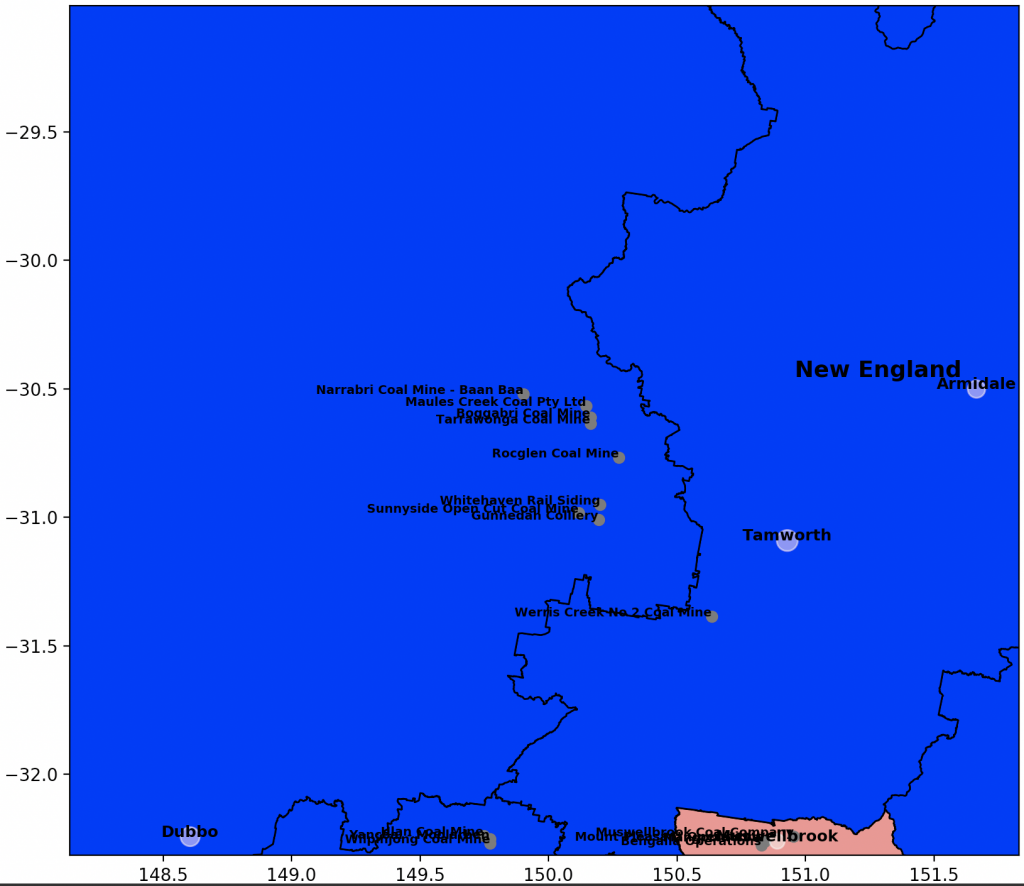

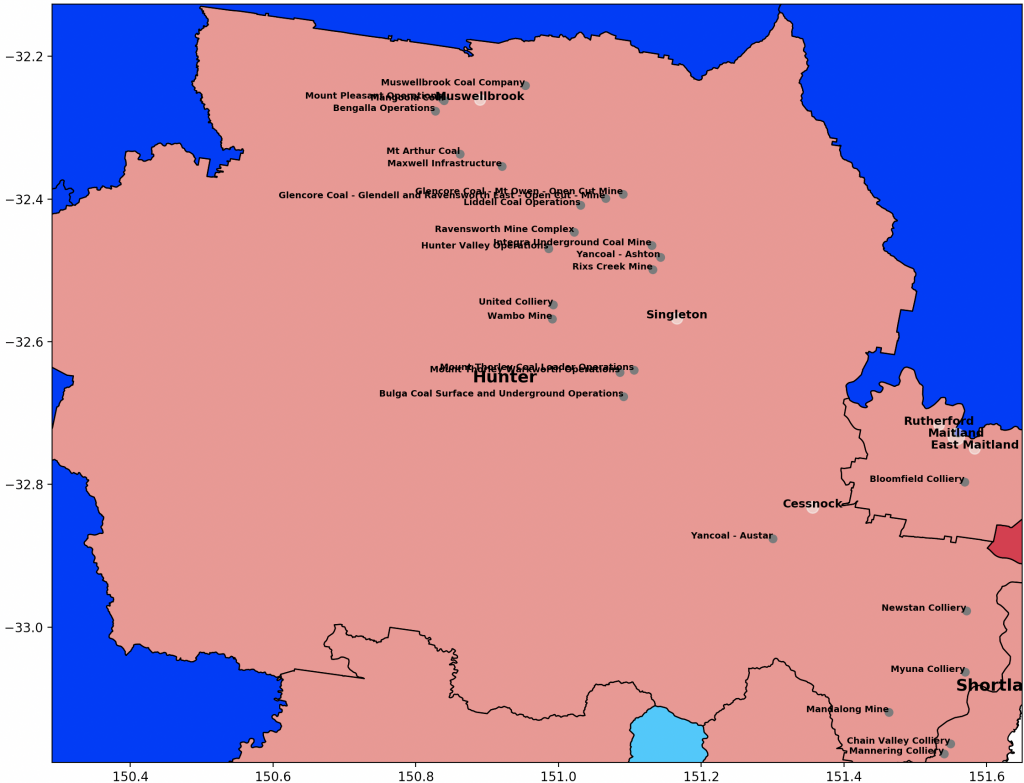

The following diagrams demonstrate coal minings concentration, and the proportion of registered voters likely to be employed in or otherwise dependent on coal mining (based on an approximation of coal mining jobs situated in-electorate or via population centres in close proximity to mining jobs in neighbouring electorates). I’ve provided estimates of total jobs from industry but rely on lower and more impartial benchmarks for employment ‘multipliers’.

Six seats are held by the Coalition, providing the base of MPs resistant to climate change policies within the Coalition – those wary of losing rural votes while being perceived as ‘anti-coal’. Labor’s wipeout in QLD at the 2019 election is widely attributed to QLD voters voting for job security).

Near Dawson, Sonoma Coal mine employs 250 and Newlands Coal mine employs 645 and Drake employs 150. The QLD Resource Council claims that mining provides 4639 full time jobs and 40,000 indirect jobs via ‘flow on benefits’ in the Dawson electorate. A more conservative estimate based on an employment multiplier of 3.9 would suggest 18,000 indirect jobs. This estimate would have approximately 25% of the sub 90K electorate owe their livelihood to mining.

In the seat of Capricornia, the QLD Resource council claims that mining provides 7070 direct jobs and 29,000 FT jobs in flow on benefit. Roughly 35% of this 103K electorate owe their livelihood to mining.

In the seat of Flynn, The QLD Resource council claims that mining provides 8,194 jobs in Flynn and 38,500 FT jobs in flow on benefits. Roughly 45% of the sub 103K electorate owe their livelihood to mining.

Between the seats of New England and Parkes, mining provides over 1300 direct jobs and perhaps up to 5200 FT jobs in flow on benefits. Roughly 5.8% of the 112K New England electorate owe their livelihood to mining.

The NSW Resource council claims that mining provides 13,300 jobs in the Hunter Valley (10K verifiable). With a multiplier of 3.9, this would equate to approximately 50K jobs in flow on benefits. Roughly 52% of the 122K electorate make their living based on mining.

While less impacted, coal mining supports significant numbers of people in two more coalition held seats with almost 8% in the seat of Calare and almost 4.5% of the seat of Hume making their living based on coal mining.

Interest Group 2: External Lobbyists(Political Donations and the revolving door)

Politics is an expensive business. Political parties are expensive to run and political campaigns are costly, with both major parties spending more in advertising than they receive in public funding.

The 2016 Federal election is the most recent example for which we have full information for declared income (it can take up to 19 months for donation information to be published: spending & receipts are declared to the AEC by June each year and published by the AEC the following February in it’s Transparency register).

In the 2016 example, the parties declared the following:

- The Federal Labour Party spent almost $35M and received $33.3M in ‘receipts’ (with $23.2M receipts being public electoral funding from the AEC). See guardian breakdown of known funders here. Spending versus electoral funding deficit: approx. $11.8M

- The Federal Liberal party spent $39.5M and received $36.8M (with $24.2M of receipts being public electoral funding from the AEC). Spending versus electoral funding deficit: approx. $15.3M

At the 2019 election, public funding may deliver $33M for the Coalition and $27M for Labor – approx. $A2.76 per no.1 vote, or $A5.50 if the party is no.1 preference in both houses) – costs are unknown at time of publication.

Membership:

The shortfall is unlikely to be made up by membership dues. It is difficult to know exactly how much membership contributes in undeclared income (memberships are not treated as donations and so not declared to the AEC) but it is likely a small proportion of the whole. Assuming membership numbers below (see next section, ‘Political Party and Ideology’) contributions of $100 per member for both the Coalition and the ALP would yield $8.0M per year for the Coalition and $5.0M per year for the ALP. Income shortfalls are not being made up by members dues and the parties are soliciting donations from different sources.

Political Donations: Declared Income:

“…the amount over which donations must be disclosed, under the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 is Consumer Price Index (CPI)-indexed and from 1 July 2018 to 30 June 2019 is $13,800…”

Source: Election funding and disclosure in Australian states and territories: a quick guide

Declared income represents only a fraction of total income (it is difficult to get an accurate picture of the scale of donations to each party as much of party income is not declared). As Hannah Aulby puts it in her 2017 publicaton: tip of the iceberg: Political donations from the mining industry:

“…Hiding political donations is not difficult, for example by donating multiple times below the $13,000 threshold. Scrutiny can further be avoided by donating through associated entities, or by payments to attend a party fundraising events…”

Source: Hannah Aulby, The tip of the iceberg: Political donations from the mining industry

Some more recent methods involve dubious new membership classes that appear to have been created to get around donation laws.

Undeclared Income:

Declared income is a diminishing share of the parties total income (in 2013-14, for example, only 25% of the Liberal party’s total income of $78.6m came from declared donations. For the ALP, only $11.6m of its total income of $46.3m came from declared donations).

I’ve been unable to locate total income figures for the parties for other years, but a recent Grattan foundation report estimated that Parties received more than $100 million from undisclosed sources in the two financial years spanning the 2016 federal election.

Quid Pro Quo:

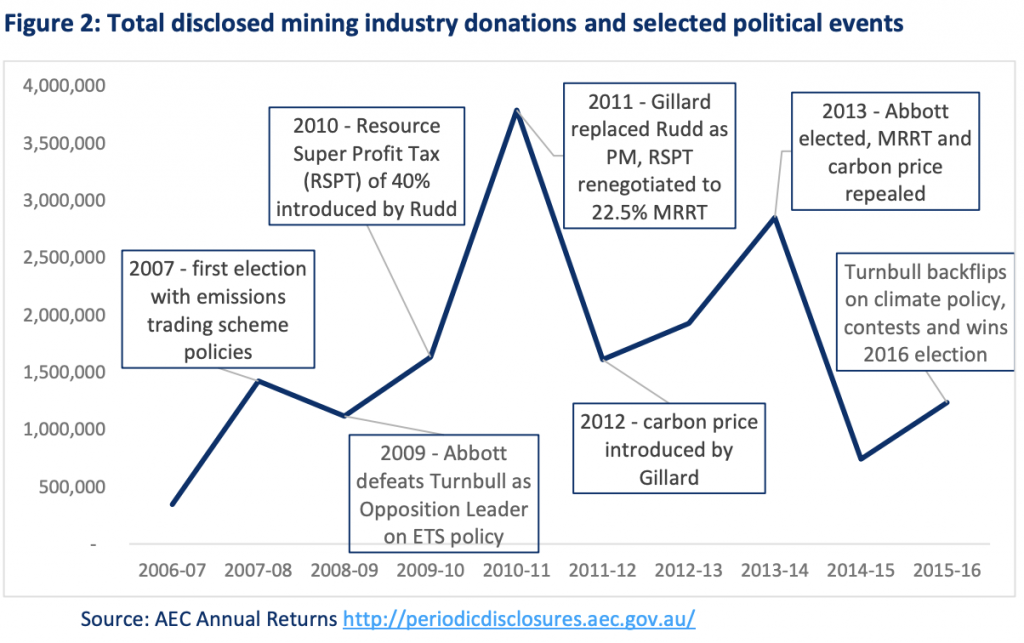

Those making either transparent or less visible contributions want something back for that donation – for example, the industry lobby group The Minerals Council of Australia (MCA) saying that they donate money to get access to politicians. With access comes influence. As Andrew Michelmore, MCA Chairman, boasted in it’s 2013 annual report:

“…The MCA was at the forefront of the debates over the carbon and mining taxes; and their abolition (expected after July 2014) will be in no small part due to the council’s determined advocacy on both issues…” – Minerals Council of Australia

Source: 2013 Annual Report, ‘Chairman’s review’.

Hannah Aulby has a good illustration of disclosed donations made to achieve policy outcomes, spiking with the election cycle. Over 81% of these donations went to the Coalition that advocated for regulation and taxation of mining companies.

In 2016-17, mining companies declared donatations of $968,343 to the main parties. Aulby also notes that declared political donations are just part of a much larger budget the mining industry uses to exert influence (with many industry groups, like the MCA, able to outspend political parties in advocacy of their interests).

The MCA continues to influence both sides of politics, with Figures like the Treasurer Josh Frydenberg quoting MCA fact sheets in 2015 to state the ‘moral case’ for coal, and the Coalition including a HELE coal plant for consideration is required in North Queensland.

A small number of donors can wield a disproportionate influence on policy – just 5 per cent of donors contributed more than half of the big parties’ declared donations at the 2016 federal election.

The Revolving Door:

Another method of influence comes from the rotation of staff from industry -> Parliament –> back to industry. The Grattan institute looked at the lobbyist register and stated that, in 2018, 36% of Lobbyists had spent time in Government (figure 2.5).

“…more than one-quarter of politicians go on to post-politics jobs for special interests, where their relationships can help open doors…”

Source: Who’s in the room? Access and influence in Australian politics

by Danielle Wood and Kate Griffiths

Technically, ‘Ministerial standards prevent former ministers from lobbying or holding business meetings with members of the government, parliament, public service or defence force on any matter for which they held ministerial responsibility for 18 months after leaving parliament’ but these standards are rather flexibly enforced and do not cover other staffers.

Interest Group 3: Political party & ideology

A narrow base:

Both the ALP and the Coalition have a narrow membership base (party officials state that the Liberal membership is 80,000 members across Australia with their coalition partner, the Nationals, ‘in the tens of thousands’. Labor states that they have 50,000 members, and the Greens approximately 12000 members). Back in 2013, News site crikey suggested that membership numbers were much lower than the parties wanted to admit.

This narrow membership base makes the parties more susceptible to capture. With small numbers of people involved in individual branches, small changes in membership have can have larger effects.

On both sides of politics, special interests and ideologues, more motivated to join a political party than the population at large, can capture a particular party branch and acquire the power to pre-select candidates and influence policy.

Unrepresentative representation:

In the Coalition case, capture has led to promotion of views outside those held by the community at large, and delayed action.

Example 1: Australia’s views on same-sex marriage were closely balanced (with a plurality opposed) in 2004 when the conservative government legislated to prevent same-sex marriage with the “Marriage Amendment Bill 2004 “. Shortly thereafter, public opinion shifted emphatically, with a majority in favour of same sex marriage.

Conservatives spent the next 13 years attempting to prevent popular will from being implemented. Several bills supporting same sex marriage were defeated, often with refusal to allow MPs a conscience vote to prevent them passing. Delaying tactics included the mendacious insistence that any change would require a referendum or plebiscite (at some point in the distant future) despite the 2004 change having been made without one. When a plebiscite was scheduled, a number of conservative members of government stated they would not respect the result of the plebiscite if it supported same sex marriage. When a plebiscite was held in 2017, the public duly voted in line with ten years polling, favouring changing the law 6l.6% to 38.4% against. Only then was a change to the law able to pass.

Example 2: In the case of climate change, unrepresentative representation continues to thwart response to climate change even as 61% say ‘global warming is a serious and pressing problem [and] we should begin taking steps now even if this involves significant costs.

Ideology:

But why has conservative politics in Australia embraced climate denialism? There most prosaic reason for the Coalition slow-walk on climate action might be One Nation. Aligning climate change policy with parties such as One Nation mitigates the danger of Coalition voters bleeding away to the fringe right (One Nation scored 3.1% of the primary vote nationwide in the 2019 election). This, together with coal jobs, might explain the stance in QLD, however it doesn’t seem sufficient to explain it nationally, given that aligning policy with One Nation also costs the Coalition mainstream votes in other states.

Tim Dean argues that to conservatives, climate change is not about science or economics. To conservatives, climate change is a moral issue. The Conversation proposed that:

“…people’s motivations prevent them from attending to and perceiving climate change evidence accurately, which influences their subsequent actions. Specifically, conservatives may focus selectively on climate data that confirm their beliefs, leading to inaction on mitigating climate change…”

Source: https://theconversation.com/climate-explained-why-are-climate-change-skeptics-often-right-wing-conservatives-123549

or as Malcolm Turnbull put it, after being deposed for the second time:

“a factual matter has become an issue of identify… climate denialism started to take root initially in the United States and what should have been, again, been a practical issue of… taking insurance became one of identity instead of fact…”

Source: Former PM and Liberal leader Malcolm Turnbull on climate denialism

A psychologist might argue that it as a case of plan-continuation-bias whereby the government will believe anything that allows them to maintain a pretence that their current plan (do as little as possible) is working, discounting all contrary evidence. In short, they just can’t help themselves – as former PM Turnbull puts it:

“…Like somebody who is told by their physician that they should lose weight, stop smoking, eat a better, healthier diet and says no, I won’t do that because I was talking to a guy down at the pub and his uncle Ernie smoked a carton of cigarettes a day and drank a dozen schooners and ate meat pies and lived to ninety… that’s essentially where we’ve got to…”

Source: Former PM and Liberal leader Malcolm Turnbull on climate denialism

This explanation fits neatly with Scott Morrison’s contorted response to the unprecedented bushfire season (nothing to do with climate change, move along, move along).

Regardless of why it has happened conservatives in Australia and the USA have signalled that acting on climate change is akin to capitulating to progressives. The Coalition have twice torn themselves apart over the issue, deposing a leader, while they were in opposition for supporting Labors climate action plan, the ETS, and dumping a PM Turnbull, while in government for pushing even modest climate policy, even after he dumped the policy to stave off a leadership revolt.

The battle being waged within the Liberal party between moderates and conservatives will continue. The conservative faction so far appearing the more ruthless (having proved willing to destroy a party candidate and threatened to damage the party unless they get their way. They’re even willing to endanger the parties electoral chances rather than seeing the moderate faction win.

I’m not going to go into branch stacking here – examples of the practice are easy to find, for both the ALP and the Coalition, come by. However, it is worrying that fringe figures are explicitly attempting to infiltrate the Coalition, one of our two dominant parties.

The public at large needs to catch-up – the mainstream needs to recapture their parties.

What can we do?

Transition away from coal, replacing coal mining jobs:

We need a plan transition away from coal domestically and for export and to replace (rather than eliminate) the jobs in coal mining areas. We could do worse than emulating Germany’s phased and orderly example by providing both workers and industry certainty and the lead time necessary to plan the transition to viable alternative employments. Given the size of the coal mining industry in the communities in which it operates, this will likely involve significant support and a longer transition than that provided to in other transition plans.

The Greens announced such a policy (with an aggressive 2030 timeline) but both major parties seem wary of the political cost.

There are enormous opportunities for transition, particularly with some government support. One example:

“…Australia is by far the world’s largest exporter of iron ore and aluminium ores. In the main they are processed overseas, but in the post-carbon world we will be best positioned to turn them into zero-emission iron and aluminium… converting one quarter of Australian iron oxide and half of aluminium oxide exports to metal would add more value and jobs than current coal and gas combined…”

Ross Garnaut, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-11-06/australia-could-fall-apart-climate-change-theres-a-way-to-avoid/11673836

Our coal-mining regions have space and a ready supply of heavy transport infrastructure, along with an abundance of solar and wind power potential. If we move fast, Australia would be well placed to lead the electrification of smelting and replace any loss in coal jobs.

Reform Donations law and police the law:

We should follow George William’s advice:

“…in addition to banning foreign donations, the federal government should adopt a NSW-style electoral finance system with caps of $5,000 on donations, real time disclosure and caps on political expenditure…”

Source: George Williams, Dean of the University of New South Wales’ law school

Limiting or eliminating donations by special interests and providing transparency is great, but we also need a Federal anti-corruption body to police politicians and lobbyists and to punish those working around the donation laws.

Stick a spanner in the revolving door:

Ministerial standards on lobbying and working with industry could be legislated, and policed by the new Federal anti-corruption body (not holding breath for this one).

Political party – Capture:

The main action I’m suggesting here is ‘participate more fully in your democracy – join a political party’. If the base membership of our major political parties grows substantially enough, the parties will inevitably be more representative and harder to capture.

Political party – Ideology:

“…It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it…”

Upton Sinclair

Respond to the conservative fears on climate change and identify outcomes of mitigation efforts that climate change deniers find important. People have strong interests in the welfare of their society, so deniers may act in ways supporting mitigation efforts where they believe these efforts will have positive societal effects the fears include:

1. We’re only a small contributor to emissions –

“…Although Australia contributes only 1.4 per cent of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions we want to play our part in meeting this challenge. But pulling our weight does not mean carrying more than our share of the burden. Only with all countries working together, carrying equitable burdens, can we achieve an effective global outcome…”

Source: John Howard Speech to Parliament 1997: https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id:%22chamber/hansardr/1997-11-20/0016%22

This is the ‘collective action’ problem. Why should we act when we can only contribute a fraction of the problem. This is a fair point although a little sophistic as the picture is less flattering if we consider Australia’s emissions per capita, where we are a much bigger contributor.

However, there are gains to be found in reducing carbon pollution, even unilaterally. For one, reducing carbon pollution and air pollution are closely related, with many pollutants entering the atmosphere due to burning of fossil fuels. The WHO states that approximately 7 million premature deaths occur annually due to the effects of air pollution, so tackling this would both positively effect community health and reduce health expenditure (& incidentally strengthens our position when negotiating carbon reductions with other nations)

If everyone waits for someone else to act first, everyone will suffer – but Australia will suffer disproportionately highly..

2. Action will have too big an impact on the economy.

“…The benefits of strong, early action on climate change outweigh the costs…Mitigation – taking strong action to reduce emissions – must be viewed as an investment, a cost incurred now and in the coming few decades to avoid the risks of very severe consequences in the future. If these investments are made wisely, the costs will be manageable, and there will be a wide range of opportunities for growth and development along the way…”

Stern Review: The Economics of Climate Change https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Economics/Faculty/Matthew_Turner/ec1340/readings/Sternreview_full.pdf

This argument has been dealt with above. Coal mining is not a large employer nationally, its economic output not irreplaceable. A carefully planned and phased approach would help both industry and workers transition with minimal disruption, and there are economic opportunities to be grasped that are far more substantial than coal.

Failing to act promises to be far more impactful and disruptive.

“…While the science is clear that any delay in implementing effective and substantial mitigation measures increases the risks of damaging climate change, it is also clear that the costs of mitigation will be higher the longer we wait. Acting early enables businesses and industries to adjust gradually to make the transition to a low–carbon economy, with time for new technologies to emerge and compete to replace old carbon–intensive technologies…”

Dr Julia Styles, Climate change: the case for action

3. We’re a special case:

“…Our economy has evolved on the basis of our abundant supply of natural resources and efficient production and processing of fossil fuels and mineral resources. Fossil fuels currently provide 94 per cent of our energy needs—far more than that of any other OECD country...We will continue to experience stronger economic and employment growth than most OECD countries… Our cities are decentralised and widely separated, resulting in high transport use per capita compared to the smaller, closely populated European Union countries…”

Source: John Howard Speech to Parliament 1997: https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id:%22chamber/hansardr/1997-11-20/0016%22

We’re not that special. Other countries with similar issues been making the same case – examples:

- Canada is a similarly geographically large country, has similar energy consumption and economic contributions from energy exports (for Canada, oil rather than coal).

Yet Canada set more ambitious emissions targets (30% below 2005 levels, rather than 26-28% and set a long term goal of 80% reduction in net emissions by 2050 (Australia has not set a longer term goal) - Indonesia, who export almost as much coal as Australia – have a slightly more aggressive unconditional Paris target 29% below 2005 levels by 2030

We are special in some ways – we are among the group of countries likely to be most impacted by climate change.

Sources:

- Commitments of each country: Climate Action Tracker,

- Shareholders of Public Companies – https://www.afr.com/research-tools/RIO/shareholders

- Electorate Information:

- Elector count by division, age group and gender

- Federal electoral boundaries GIS data as at January 2019, AEC spatial data (free download)

- Towns of the Mining Boom

- Size and location of coal mines (proved a more comprehensive and accurate source than google etc!)

- Economic data on size of the coal industry:

- IEA Atlas of Energy

- Resource and Energy Quarterly publications, June 2019

- Resources and Energy Quarterly June 2019 Thermal Coal.pdf

- Econobabble: How to Decode Political Spin and Economic Nonsense

- Fact Check – Are there really 54,000 people employed in thermal coal mining?

- McKinsey and Company, Global Energy Perspective 2019 Reference Case

- Australia Institute Publications:

- Tax Transparency Data:

- Donations:

- AEC – Financial Disclosure

- The tip of the iceberg: Political donations from the mining industry by Hannah Aulby

- https://www.tai.org.au/content/tip-iceberg-political-donations-mining-industry

- Who’s who in the room? Access and influence in Australian politics

- ABC’s Searchable db of declared donations, 2015-16

- Benefits of acting:

- CSIRO & BOM publications & Tools:

- Climate change and Ideology: