The Early Years:

Climate change began garnering scientific, media and public attention in Australia in the mid 80s…

Following two major climate change conferences and community forums organised first by the CSIRO in 1987 and again, along with the federal Commission for the Future, in 1988, a study called the Australian public the best informed on the planet on this topic. This was also stated publicly at a United Nations’ Global 500 Award ceremony during that period.

Source: Global Warming and Climate Change – what Australia knew and buried… by Maria Taylor.pdf

So what, exactly, has been the Australian federal government’s response over the past thirty plus years?

1984-1991 – Wait and see – The Hawke government and Liberal opposition:

Ex-science minister Barry Jones claimed that the Hawke Government knew about the risks of climate change in 1984 but did little about them). However, both public and politicians began taking more notice of Climate change around the publication of the first UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (a.k.a. IPCC) report in 1990

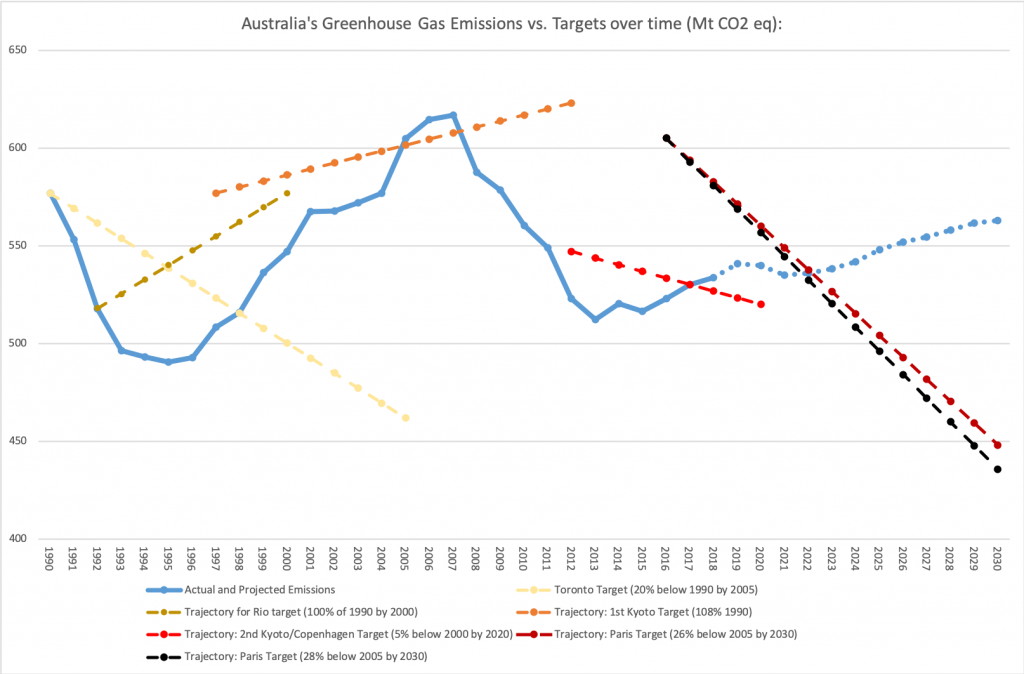

Both sides of politics saw the need to act (or at least be seen to be act). In October 1990 the Hawke Labor Government adopted a ‘interim planning’ emissions reduction target aiming to lower greenhouse gas emissions 20% below 1988 levels by 2005. This came with a soon-to-be-familiar-caveat that:

“…the Government will not proceed with measures which have net adverse economic impacts nationally or on Australia’s trade competitiveness in the absence of similar action by major greenhouse gas producing countries.”

Source: https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/download/media/pressrel/2209922/upload_binary/2209922.pdf;fileType=application%2Fpdf#search=%22media/pressrel/2209922%22

The Liberal Party opposition (under leaders Andrew Peacock and John Hewson) went to the next two elections with a comparable reduction target, even committing to cutting greenhouse gas emissions sooner (by at least 20 per cent by 2000 if they won office).

‘Other’ things to worry about – The Keating Government (1991-1996)

By 1991, the Labor Government had a new leader, Paul Keating, and a recession had pushed climate change to the back of both voters and politicians minds.

Australia signed the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) in Rio in 1992 (where Australia was the only OECD country not to send their Head of government), and considered a Carbon Tax, but took little action, sticking with Hawke’s “no regrets” policy. Australia would continue to consider only measures that involved cutting emissions without any adverse impact on the economy or trade competitiveness.

The Denial years: The Howard government (1996-2007)

The Howard Liberal Government succeeded Keating in 1996 and begun the Australian conservative pattern of being actively hostile to climate action (while being aware of the need to be seen to act).

In his “Safeguarding the Future: Australia’s Response to Climate Change” initiative in 1997, the Howard Government announced measures intended to slow the growth of emissions from 28% to 18% by 2010 (based on 1990 figures). Further action was limited, with the government committing $A180 million over five years (annual whole of government expenditure at the time being around $A200 billion) to seed a renewable energy innovation fund and to obliging electricity providers to generate an additional 2% of electricity to be sourced from renewable sources (by 2010).

The clear lack of ambition was bad, but the sabotage of global action was worse. The Howard government attended the December 1997 Climate conference in Kyoto, but argued that Australia was a special case, and should be allowed to increase its emissions when almost everyone else* was committing to cutting emissions (*Iceland, 10% and Norway, 1% also argued that they should be allowed to increase emissions).

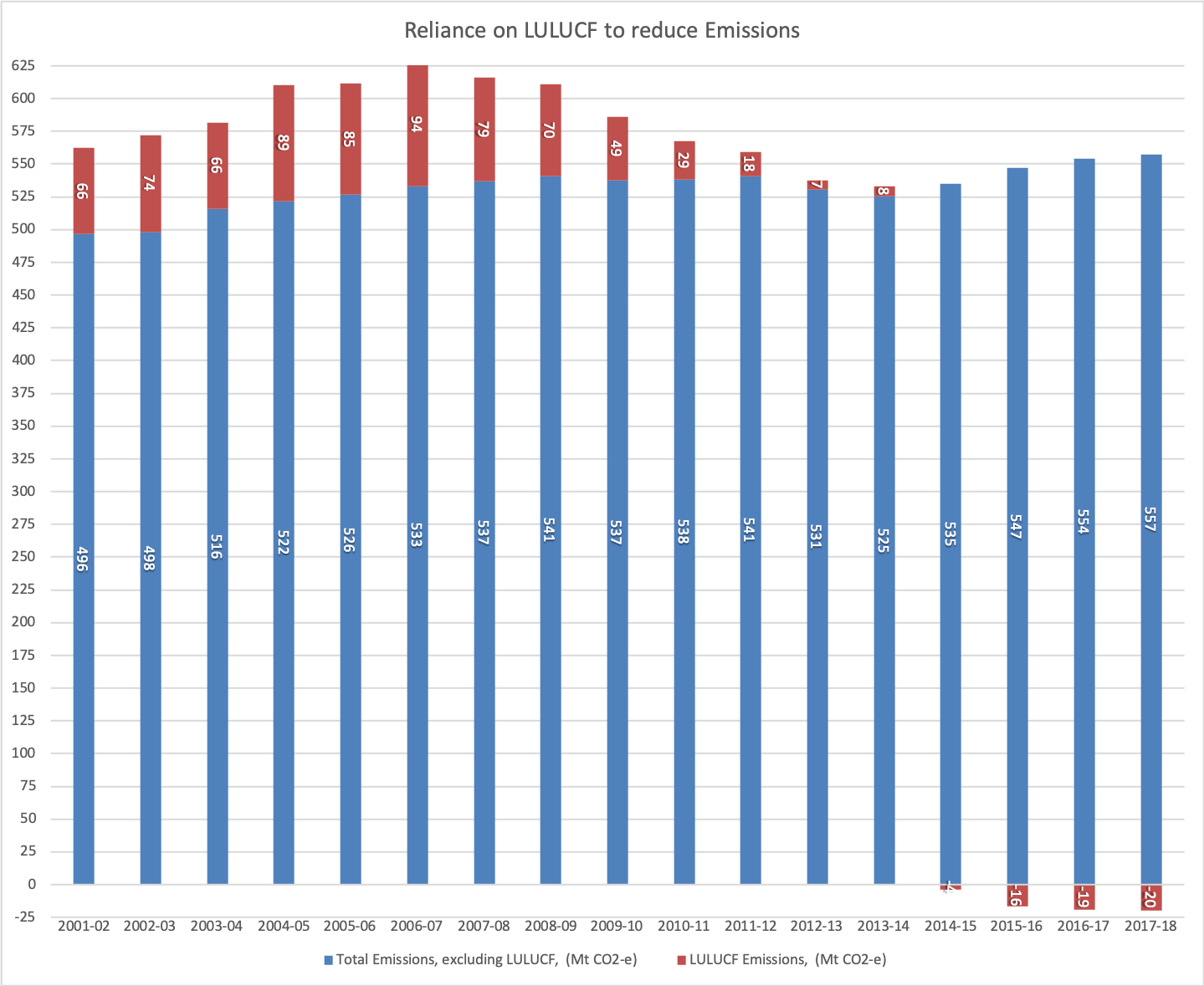

At the end of the summit, Australia’s lead negotiator, Robert Hill, demanded a last minute change so that Australia could include land clearing in emissions accounting, artificially inflating Australia’s starting emission number:

“…Hill knew that land clearing in Australia had declined sharply between 1990 and 1997 because there had been a spike in 1990, mainly in Queensland. So an 8% increase would be on top of an extraordinarily high and artificial 1990 base.

Source: https://theconversation.com/australia-hit-its-kyoto-target-but-it-was-more-a-three-inch-putt-than-a-hole-in-one-44731

Hill understood that with the inclusion of the Australia clause, the nation’s emissions from burning fossil fuels could rise by 25-30% while overall emissions would still come in at under 8%”

After setting a woeful target, Australia signed and then refused to ratify the Kyoto protocol. This made the target aspirational and not legally binding. The familiar logic behind the move, articulated by the PM:

“…It is not in Australia’s interests to ratify the Kyoto protocol. The reason it is not in Australia’s interests to ratify the Kyoto protocol is that, because the arrangements currently exclude—and are likely under present settings to continue to exclude—both developing countries and the United States, for us to ratify the protocol would cost us jobs and damage our industry…”

Source: https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id:%22chamber/hansardr/2002-06-05/0030%22

In April 2001 the Mandatory Renewable Energy Target scheme (MRET) started, incorporating the Prime Minister’s 1997 pledge on renewable energy production. By 2002, Australia’s share of renewables in energy production had increased from roughly 6% in 1997 yo 7.9%. No further target was announced.

Little other action was taken. Emission trading schemes (ETS) proposals came and went until the 2007 election, when the long running Millennium drought presence across south-eastern Australia made it expedient for both parties to rediscover the importance of the climate issue. The Howard government was defeated at the 2007 election, in part, due to the more ambitious climate change proposals by the Rudd Labor opposition).

Warfare: The Rudd (2007-2010) / Gillard (2010-2013) Labor governments and the Turnbull / Abbott opposition

The Rudd Labor government succeeded Howard in 2007 describing climate change as “the great moral challenge of our generation”.

They ratified the Kyoto protocol (committing Australia to keeping emissions to no more than 108% of its 1990 emissions level by 2012) but kept the dodgy LULUCF accounting treatment.

They introduced the Clean Energy Initiative, a $A4.5 Billion scheme with $A1.6Billion for solar to add an additional 1,000 MW of solar generation capacity and and 465 million to establish Renewables Australia to support leading-edge technology research. However, over half was dedicated to Coal Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS) which has a long history of failure.

Rudd tried, and failed, to get an Emission Trading Scheme (ETS) through parliament. The left aligned Greens Party notoriously didn’t support the ETS policy, objecting that the targets were too modest. This left the Opposition Liberal Party, which had somewhat unenthusiastically promoted their plans to introduce their own ETS at the preceding election. Their leader, Malcolm Turnbull, who had managed to successfully amend the Labor ETS policy, was then deposed by his party, rather than support Labor’s ETS. The new opposition Liberal leader, Tony Abbott, characterised the ETS as a “Great big tax” on everything, and the legislation was voted down in 2009 and not pursued further by the Rudd government.

In 2009, the government increased the Renewable energy target, targeting 20% of Australia’s electricity to be provided from renewable sources (setting a target of 45 000 GWh).

Fast forward through a Labor leadership change and a closely fought election…

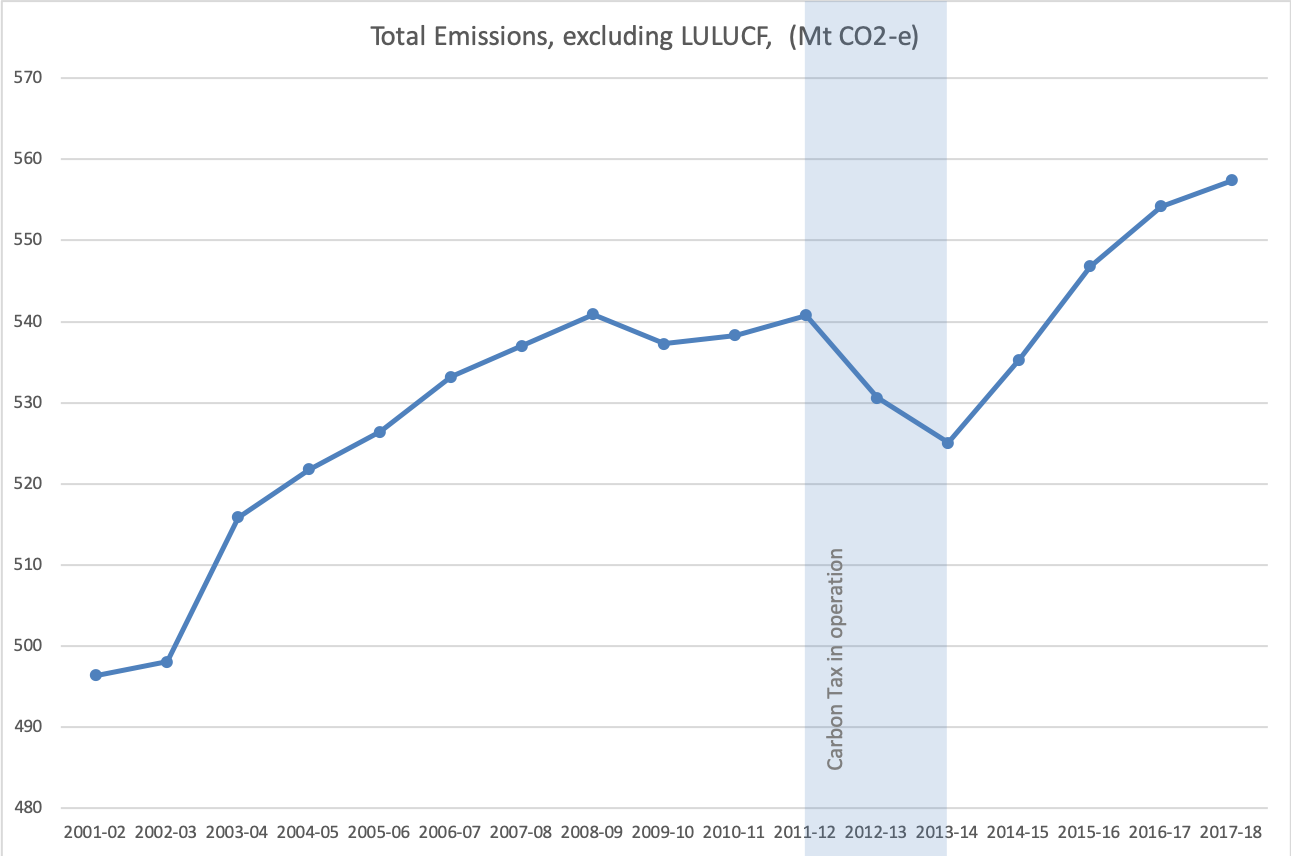

In 2011 the Gillard Labor government, supported by the greens party, introduced a Carbon tax in 2011 (the Clean Energy Act 2011) which came into effect on 1 July 2012 and operated until it was repealed in June 2014.

In 2012 it created the $10 billion Clean Energy Finance Corporation (CEFC) a fund dedicated to investing in clean energy.

The limited evidence we have (given that the carbon tax only operated for two years) suggests that both of these initiatives had some effect.

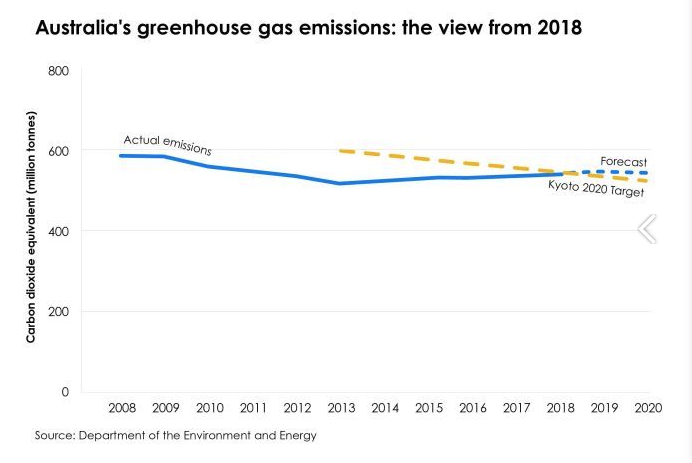

Source: Department of the Environment and Energy

What problem? The Abbott years (2013-2015):

The new Liberal Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, had deposed his liberal party predecessor and fought an election on the premise that the “cost” of fighting climate change was not worth it. Abbott had espoused the view that the science around climate change is “absolute crap.”

“…The argument is absolute crap. However, the politics of this are tough for us. 80 per cent of people believe climate change is a real and present danger. ..”

Source: http://www.theaustralian.com.au/politics/the-town-that-turned-up-the-temperature/story-e6frgczf-1225809567009

Australia was back to wanting to be seen to be doing something while, in actuality, doing little and minimising the cost and disruption to industry.

Previous policies were replaced by the “Direct Action” program, which offered $A3 billion in incentives for business and consumers to reduce emissions to 5% below 2000 level. Modelling suggested that it was unlikely to achieve even the 5% emissions target, but no revisions were countenanced. The policy was criticised by the former Liberal leader, Malcolm Turnbull, who observed that it involved spending billions of taxpayers’ dollars to pay farmers to create offsets so industry could freely pollute.

A number of editorials have examined the effectiveness and cost of the Direct Action scheme and pointed out further problems:

- vegetation projects (regenerating degraded habitat, tree-planting etc.) expected to deliver two-thirds of the cuts have problems:

- The permanance period of 25-100 years assumed in the contracts are optimistic (in a land of frequent and increasingly severe bushfires and droughts).

- accuracy – there is no way of knowing if “avoided deforestation” schemes (in which landowners are paid to not clear their land) are genuinely preventing land clearing.

- Inefficiency: in some cases, it would have been cheaper to buy the land rather than pay landowners to protect it

In any case, the Abbott Government had a new policy and immediately began with legislation to dismantle the previous government’s policies, beginning with the repeal of the Carbon Tax (a.k.a. the Clean Energy Act 2011) and it announced its intention to shut down the government’s Clean Energy Finance Corporation. The incoming Treasurer, Joe Hockey ordered the CEFC to cease investments. The new Environment minister announced plans to dismantle the Climate Change Authority (CCA).

After a number of attempts, The Clean energy act (2011) was successfully repealed in June 2014 ending the carbon tax period. The Climate Change Authority and Clean Energy Finance Corporation CEFC proved more resilient, with bills for their abolition voted down three times.

Unable to abolish the profitable and effective CEFC, Abbott announced in July 2015 that he would ban the CEFC from investing in wind power and rooftop solar.

In 2015, after negotiation with the Labor opposition, a new Renewable Energy Target was released. The RET is reduced to 33,000 gigawatt hours, or 23.5%, of the estimated electricity generation for 2020 (reduced from the previous 45 000 GWh)

In it’s final report in 2015 the CCA had recommended a 2025 target of 30% below 2000 levels. The Abbott Government subsequently announced it’s Paris post-2020 target, matching the USA’s commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2030, but without legislation to enforce it.

Lost years – Malcolm Turnbull 2015-2018

The liberal party dumps Tony Abbott and elects a new leader, Malcolm Turnbull, who Abbot had previously deposed for supporting emissions trading whilst in opposition. Turnbull won the leadership, but was wary of conservatives in his party and obliged to continue previous policies while pushing for smaller, incremental change.

In September 2016 two tornadoes tore through SA, bringing down two high voltages transmission lines and causing several failures across the transmission network. The ABC provides a great summary of events: as faults grew, output from nine wind-farms in SA fell by 456 megawatts over a period of less than seven seconds as protection features at the wind farms kicked in. When the wind farms unexpectedly reduced their output, the Heywood Interconnector from Victoria tried to make-up the transmission shortfall, and then subsequently activated a special protection scheme that tripped it offline.

Blackouts ensued. Conservatives blamed ‘unreliable’ renewable energy and supporters of renewables blamed the storm and Australian Energy Market regulator. After this, any path to emission reduction also needed to reassure that renewable energy could deliver reliability.

Consumers were also seething that power prices that had been rising inexorably, across the country.

Prime Minister Turnbull’s response was the National Energy Guarantee (NEG) which was aimed to delivering cheaper, more reliable power and also lowering carbon emissions. The policy was supported by the cabinet, but enough backbenchers rebelled that the policy was in doubt. Turnbull was stuck between the Labor opposition (who wanted a higher emissions reductions targets and no support for additional coal generation) and conservatives backbenchers in his own party who were aghast that the NEG intended to legislate for carbon emissions reductions… and who also wanted support for additional coal generation.

The Liberal leadership was soon again in doubt. By the end of August, Turnbull had shelved any move to implement the 26% reduction in emissions because it could not get the numbers to pass legislation in the House of Representatives. Another leadership spill ensued, and by September 2018 a new leader, Scott Morrison, led the Liberal party.

Nothing to see here – move along – Scott Morrison 2018 ->

Morrison supported the 26% Paris climate goals, but not in such a way that might make them enforceable. In language that is very familiar to Australian’s he noted:

“…Our commitment stands, but we won’t be legislating it…” & “…The NEG is dead, long live reliability guarantee, long live default prices, long live backing new power generation…”

Source: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/neg-dead-morrison-to-ditch-energy-legislation-but-keep-paris-targets

In an interview with Alan Jones early in his tenure he continued to insist, that Australia would meet it’s Paris agreement goals, saying “We met the first round of targets at a canter and this next one is out to 2030. Now, that discussion isn’t going to change anybody’s electricity prices, and that’s what I’m focused on.”

The only remaining Federal programs aimed at emission reductions were now the government’s Abbott-era emissions reduction program “Emissions reduction fund (ERF)” and the RET. This ERT was rebranded as the “Climate Solutions Fund” and it was provided an additional $2B in funding, despite having not spent its existing budget and despite emission abatements based on the program appearing to have flatlined.

In September 2019, Australia reached the diminished Renewable Energy Target of 33000 GWh of renewable generation (out of 260,000 GWh), ending a Federal government scheme that provided subsidies to wind, solar and hydro power projects. No further federal target has been announced.

Not-so-great-expectations, as at Dec 2019:

The current Federal liberal government exhibits behaviour that suggests that it is aware of the potency of the issue of Climate change, even as they dispute the urgency or the science (see ipcc 2018 summary for policymakers Projected Climate Change, Potential Impacts and Associated Risks). Some examples of recent government behaviour supporting this assertion:

- Cynical timing in releasing climate data on Christmas eve, before football finals (and while the Banking royal commission was delivering his interim findings into the financial services industry or seeking to avoid releasing the data at all

- The PM’s response to a furious speech by Swedish environmental campaigner Greta Thunberg at the United Nations Climate Summit, implying that people had lost ‘context’ and ‘perspective’, and had subjected their kids (like Greta) to ‘needless’ anxiety

- The PM’s response in Parliament when told of school students participating in a climate-strike “What we want is more learning in schools and less activism in schools.”

- The PM threatening that the government would seek to apply penalties to those targeting businesses who provide services to the resources industry, highlighting the “worrying development” of environmental groups targeting businesses or firms involved in the mining sector with “secondary boycotts”.

- Attempting to divert commentary regarding the link between climate change and the frequency and severity of drought and fires (implying the fires were due to ‘eco tourism’ was somehow blocking parks management of fire fuel load) and castigating those who raised the link on the grounds that Australia only accounts for 1.3% of global emissions. Worth reiterating that scientists have been making this link for over 20 years: e.g. the CSIRO in 1995 “…any impacts of climate change are likely to be experienced firstly, and most significantly, in terms of changes in the frequency and magnitude of extreme events, namely floods and droughts..” & CSIRO in a 2005 study assessing potential changes from fire-weather risk, associated with climate change in south-east Australia)

- Senior government figures like Liberal MP Katie Allen & Minister for Energy and Emissions Reduction, Angus Taylor touting ‘success’ in lowering emissions using falling “Emissions per capita” to a domestic audience (progress against Kyoto & Paris targets are measured in total emissions) whilst simultaneously using Australia’s low share of total emissions to international audiences to justify Australia’s reticence to act (Australia is the top few per-capita emitters in the world but accounts for just 1.3% of total emissions).

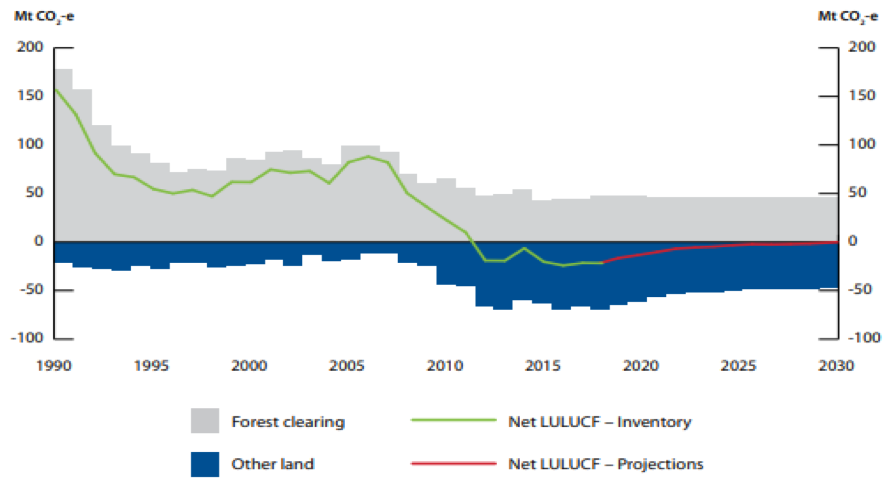

- Their insistence that nothing more needs to be done, despite evidence to the contrary: emissions reduction based on the ERF program appearing to have flatlined and tje government is relying on LULUCF to show emissions abatement (they’ve been offsetting rising emissions in other areas since 2014-2015)…

But further abatement may not be possible, based on the forecasts:

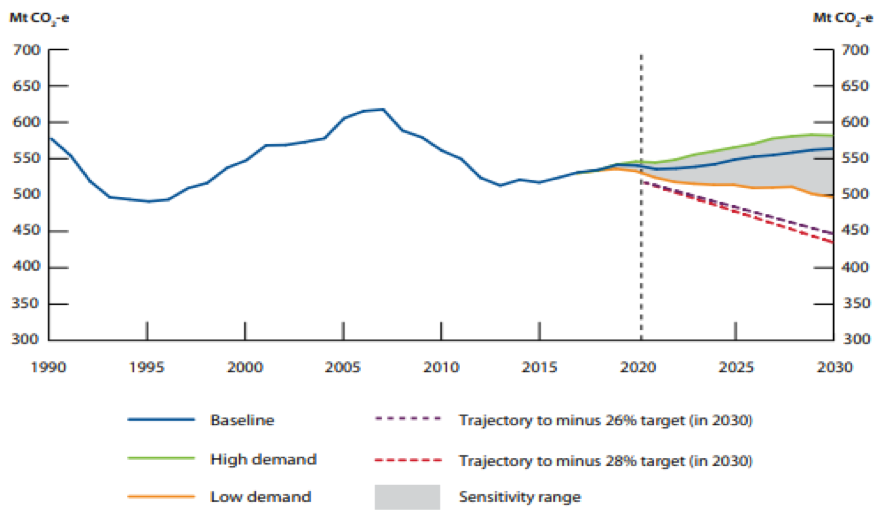

Source: Department of the Environment and Energy – Australia’s emissions projections 2018 figure 14

Tellingly, the government continues to insist that it is meeting it’s Kyoto Period2 target because it is under the total cumulative budget for the period (4488 MTCO2, 2013-2020). However, it omits embarrassing contextual information, such as:

- that the trend is going in the wrong direction – Australia will finish the Kyoto2 period exceeding the desired level, 524Mt CO2 annual emissions (5 per cent below 2000 levels) in 2018 and forecast to do so again in 2019 and 2020).

- that we are only meeting the target because years early in the decade came in under budget (such as two years where a carbon tax was in operation!)

- we’ve even used accounting tricks, such as a “carry-over” credit of 128 Mt CO2 for ‘over-achieving’ on the modest Kyoto 1 period, to meet the target.

All of this is setting Australia up for an epic fail for the Paris 2030 targets:

The Future:

Clearly the trend line is going in the wrong direction. The Federal government is ominously silent about how it will meet the Paris 26-28% 2030 target, and it’s worth reiterating that this was an inadequate target in the first place: The Latest UN IPCC report states that Global emissions must fall by 7.6% every year from now until 2030 to stay within the 1.5C ceiling on temperature rises that scientists say is necessary to avoid disastrous consequences:

“…Our collective failure to act early and hard on climate change means we must now deliver deep cuts to emissions [of] over 7% each year, if we break it down evenly over the next decade. This shows that countries simply cannot wait…”

Inger Andersen, executive director of UNEP, Source: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/nov/26/united-nations-global-effort-cut-emissions-stop-climate-chaos-2030

Well… this is all a bit depressing… but what can we do?

Fortunately, the policy constipation only seems to be afflicting the Federal government. almost all the states and territory governments in Australia are acknowledging the need to do more and are, in many cases, both planning and opening their wallets to pick-up slack from their federal counterparts:

- The ACT is pushing for 100 Renewable energy by 2020.

- South Australia now routinely sources more than 50% of it’s power from renewables and is aiming for 90 per cent renewable energy generation in the mid 2020s and a net renewable energy exporter in the 2030s. It is investing in new interconnection and storage technologies such as hydrogen to get around the issues of dispatchable power)

- The Victorian Government’s Renewal energy target (VRET) of 40 per cent by 2025 and 50% by 2030.

- QLD is targeting 50% renewable energy by 2030

- NSW is rolling out ‘Renewable energy zones’ to make development of Renewables easier, and sees firmed-renewables as the cheapest way to replace its aging coal fired generators

- WA – The Western Australian Government announced a new policy approach that seeks to limit greenhouse gas emissions from major projects as part of its “aspiration” to move all sectors of the state’s economy to producing net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050

Australian households are also playing their part. Australia has the highest proportion of households with PV systems on their roof of any country in the world and installations are growing rapidly, with falling costs and state subsidies boosting the number of solar and battery installations. In fact, solar uptake has been so rapid that it’s created other issues for the Australian Power Distribution network service providers to solve.

Lastly, governments do change. The last government to obstruct the public’s desires to act on climate change during the millennium drought didn’t do so well in the 2007 Election (the Prime Minister at the time, John Howard, being the second Prime Minister to lose their own seat at an election). If they are paying attention, then the public is again getting increasingly restless for action…

For More information:

The Australian Parliamentary Library has a comprehensive history of Australian policy action on climate change: https://www.aph.gov.au/About_Parliament/Parliamentary_Departments/Parliamentary_Library/pubs/rp/rp1516/Climate2015

& Australia and Greenhouse Policy- A Chronology

Source Data for graphs from:

- National Greenhouse Gas inventory http://ageis.climatechange.gov.au/NGGI.aspx

- Department of the Environment and Energy Climate Change Publications